By Zachary Margulis-Ohnuma

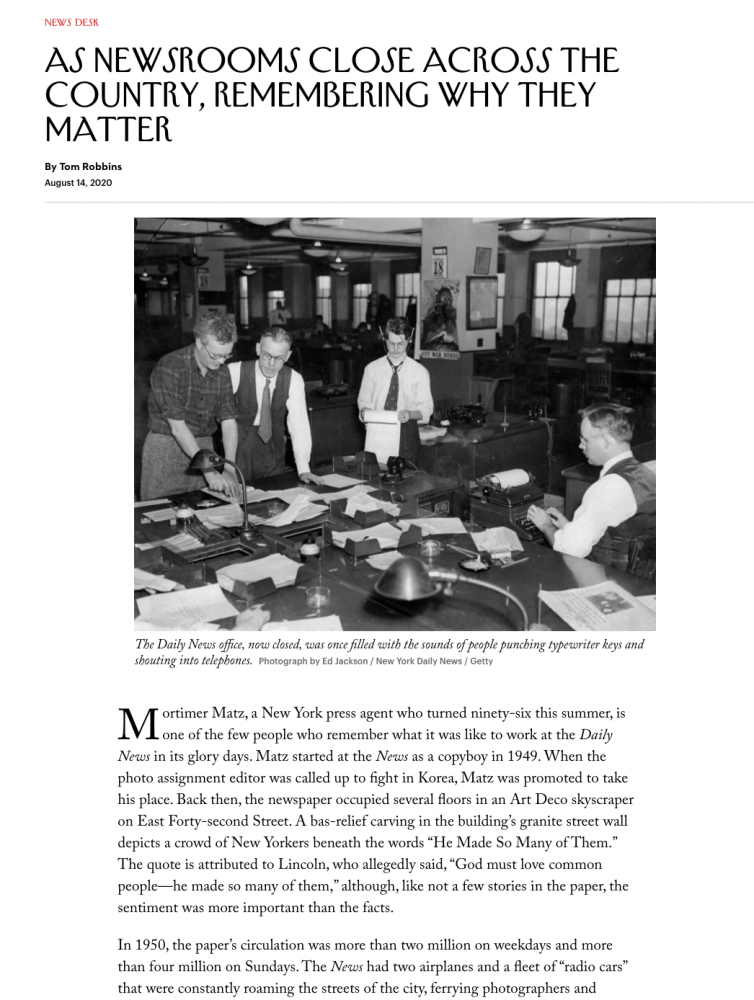

A year or so working as a reporter at 220 E. 42nd Street around 1993 completely changed my life. It was part of nearly four years I spent on the staff at the Daily News, once one of the largest-circulation publications in the world but already in the midst of a long, slow decline. I was honored to have met most of the “oddballs and brilliant people” that my sometime client, mentor, and extraordinary professor of journalism Tom Robbins describes in his wistful remembrance in the New Yorker.

I was humbled every day to be part of a paper going out to hundreds of thousands of readers in the world’s greatest city. I sat behind Jerry Capeci as he worked his FBI sources to figure out who set off the enormous bomb in the WTC parking garage. Gene Mustain and I wrote about that era’s heroin epidemic: “Smack is Back.” Before we moved to the Bronx Bureau with Bob Kappstatter and Rafael Olmeda, my dearly departed friend Raphael Sugarman managed to trade food stamps for drugs in the wintertime on 125th Street and we wrote it up from that seventh floor newsroom.

For two miserable weeks, I filled in for the amazing lobster shift reporter, Tom Raftery; after everyone else went home, my biological clock was so out of whack I could scarcely think, let alone think straight enough to report to the morning editors or write anything coherent. I worked for Don Forst the summer before, then interviewed him when New York Newsday shut down. I “interviewed” Michael Jackson as he munched on sushi with Lisa Marie Presley and reported on the conception of Lourdes Leon. I worked and competed with Rob Speier, the wunderkind who lasted only about a year, was profiled by 48 Hours prancing on 42nd Street, and then left to become a real estate mogul.

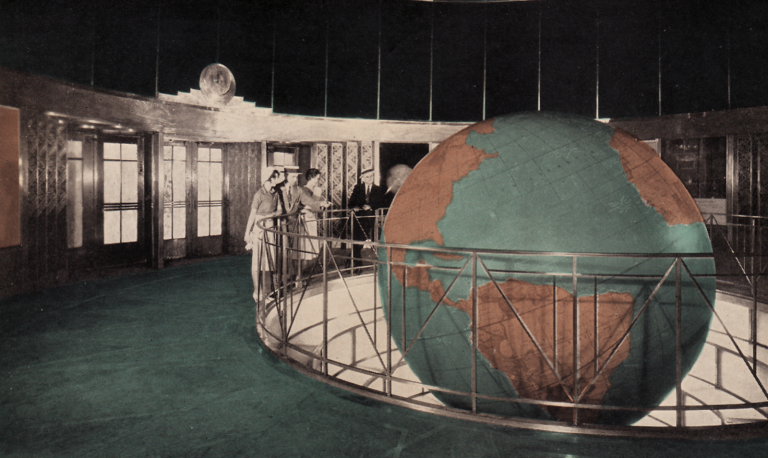

I worked in various offices at the Daily News, but there was nothing like going past that twelve-foot Superman globe on 42nd Street, pink or green NYPD press pass flapping around your neck, notepad in hand. It was Jimmy Olsen, all in black and white. Sometimes, not always, poetry rolled out as reporters called in to re-write guys like Corky Siemaszko and the bow-tied Stephen McFarland. Editors conjured up headlines that would stir up our readers while they rode the trains to work. My favorite, of course, was “Misspent Youth” which described my 1995 story about a non-existent youth group used to funnel state money to a political campaign (the treasurer was Carl Heastie, now speaker of the New York State Assembly). When we moved from the dead center of New York to deep West 33rd Street, the “soulless” building rumored to have a roller rink on the top floor, it was not quite the same.

Whether as newspaper-people or as lawyers, we lose something essential working alone, over Zoom, away from colleagues and friends. Courtrooms are slowly, slowly starting to re-open. Even jails, hotbeds for the spread of virus, are opening up. Our clients desperately need to see our faces, to know that no one is listening in through the electronics, to have someone to trust. But our readers never saw our faces — that was for television. The live action in newspapers was out on the street or in the newsroom.

As print publications trim costs, real estate expenses soar, and we learn to do everything remotely — just not as well — newsrooms will probably be a permanent victim of the pandemic. Unlike newsprint and gasoline cars, which are wasteful and dirty, newsrooms serve an essential, unseen purpose which cannot be replaced. A young reporter who has to check in with colorful characters at The News Building writes better copy than one who sits in her pajamas at home.

The world needs newsrooms.